Why a Big Change Isn’t the Best Fix

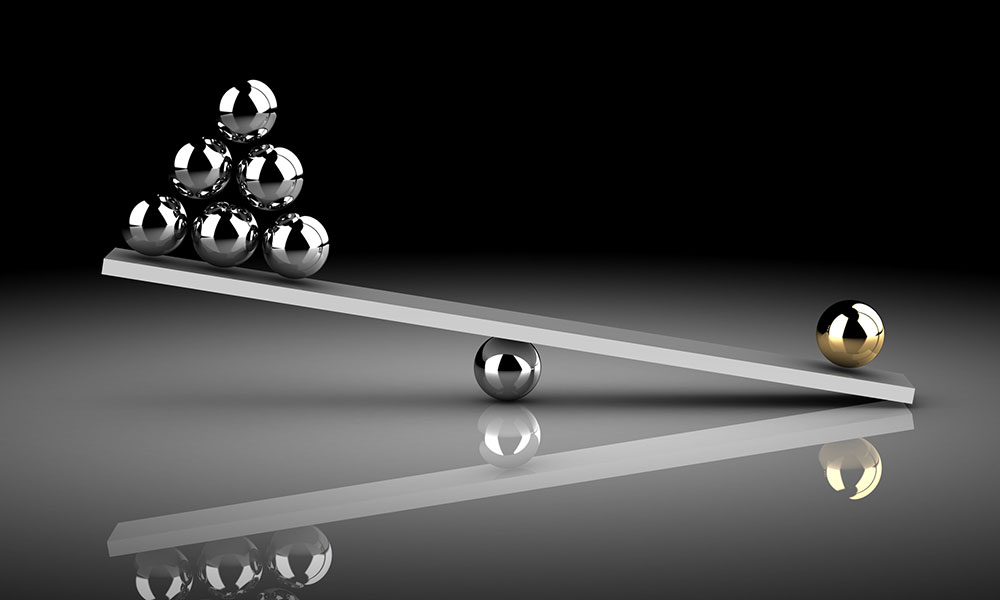

CEOs are challenged to innovate, but a recent poll suggests that what’s really needed is stability and trust.

CEOs may get the best office, but their reputations are in the trash.

That’s the takeaway—or one takeaway, anyhow—from the recent Harris Poll survey of public opinion of corporate leaders. Half of all respondents rated today’s CEOs, as a class, as “bad.” And though millennials have a rosier view of them than other groups (33 percent rank them as “good”), the C-suite doesn’t get much love these days across the political and demographic spectrums.

The public isn’t looking for a cowboy CEO.

There are a whole host of reasons why the public might feel that way. In down economies CEOs are perceived as the people who take the jobs away, while in good times the popular image of the corporate exec is less that of a leader than a rapacious profiteer. A scandal or two usually fills the business pages and nightly news reports. And a sitting President who’s a former CEO with historically low approval ratings likely doesn’t help.

But one suggestion the Harris Poll makes is that the public is suffering from a bit of innovation fatigue. Last week, AssociationsNow.com’s Ernie Smith pointed to an interesting comment on the poll from Harris Poll VP Wendy Solomon, interpreting the poll’s findings. “Consumers first and foremost look for human decency traits—trust, accountability, ethics, competency, respect,” she says. “The public isn’t looking for a cowboy CEO; it’s not about brazen, visible risk-takers. They seek a more measured individual in the leadership seat.”

To be clear, a CEO who’s willing to take risks has plenty of value: Among the attributes that respondents were asked to rate are “innovative” and “a clear vision for the future.” And though the top-ten list of companies that scored highest in terms of reputation mostly includes old-school retailers (Publix, Wegmans), manufacturers (3M, Johnson & Johnson), and entertainment companies (Walt Disney), there are trailblazing tech firms too: Amazon, Tesla, Apple, Google.

For a lot of people in the association world, companies like that last group those tend to trigger the we-can’t-do-things-the-same-old-way impulse, with exhortations to “shake things up” and “run more like a business.” But that mix of old and new companies suggest that what matters isn’t recklessly blowing up models (which can spell trouble for overly aggressive CEOs) but looking for ways to more creatively serve old-fashioned needs.

Consider Amazon. In an essay published last week by the Harvard Business Review, Drucker Institute executive director Zachary First points out that the online retailer’s storied innovative moves tend to have a conservative side: For instance, it focuses its money on long-term goals instead of short-term, investor-pleasing moves, and has a Weekly Business Review to provide close oversight on operations.

First deploys an unlovely metaphor to make the point that change should be a function of larger strategic goals: “The task of the executive managing change today is thus not to turn the entire organization into an intestine by extracting value, and discarding waste, as quickly as possible,” he writes. “It is to ask of change in any one area of the business: At what pace? And to what end?”

First prescribes a go-slow approach to anything that has the word “change” attached to it. “Better to pursue cumulative advantage with your employees, just as if they are your customers,” he writes. “Change slowly through small-scale experimentation, and don’t roll out anything organization-wide until you have evidence that it works.”

I’d add on top of that, though, that any conversation about change involve a discussion about what’s valuable and what shouldn’t be jettisoned. Associations have a cybersecurity problem, but that doesn’t mean they ought to dump their computers, of course; they just need to get smarter about how they think about security. Associations with education programs that don’t do much for the bottom line don’t have to explode credentialing altogether, but they might look for ways to expand what they’re teaching to a broader audience.

People who look at CEOs and find them wanting aren’t being critical of change—just of the kind of reckless, needless change that makes them untrustworthy as leaders. The Harris Poll suggests that people tend to closely scrutinize a company’s behavior: “The public is interested in how a company engages with the world,” according to the report. “They increasingly serve as advocates and saboteurs, presenting a level of complexity (…and unpredictability, …and messiness, …and importance) to reputation managers that is unprecedented.” That’s surely no different for association members and stakeholders. But evidence that the leadership knows its direction and has a steady hand on the wheel can afford you some understanding when you do take a risk.

How do you balance stability and risk-taking at your organization? Share your experiences in the comments.

(iStock/Thinkstock)

Comments