Marketing the Future: Learn From the Mac’s Initial Missteps

We vividly remember the genius marketing of the original Apple Macintosh in 1984—but we forget that the device initially fell flat with business customers. The reason it did should sound familiar to a lot of tech decision-makers.

We vividly remember the genius marketing of the original Apple Macintosh in 1984—but we forget that the device initially fell flat with business customers. The reason it did should sound familiar to a lot of tech decision makers.

On December 31, 1983, a minute-long ad played on a local CBS affiliate in tiny Twin Falls, Idaho.

It was something of an inauspicious start for the 60 seconds of film that became one of the most iconic advertisements in American history.

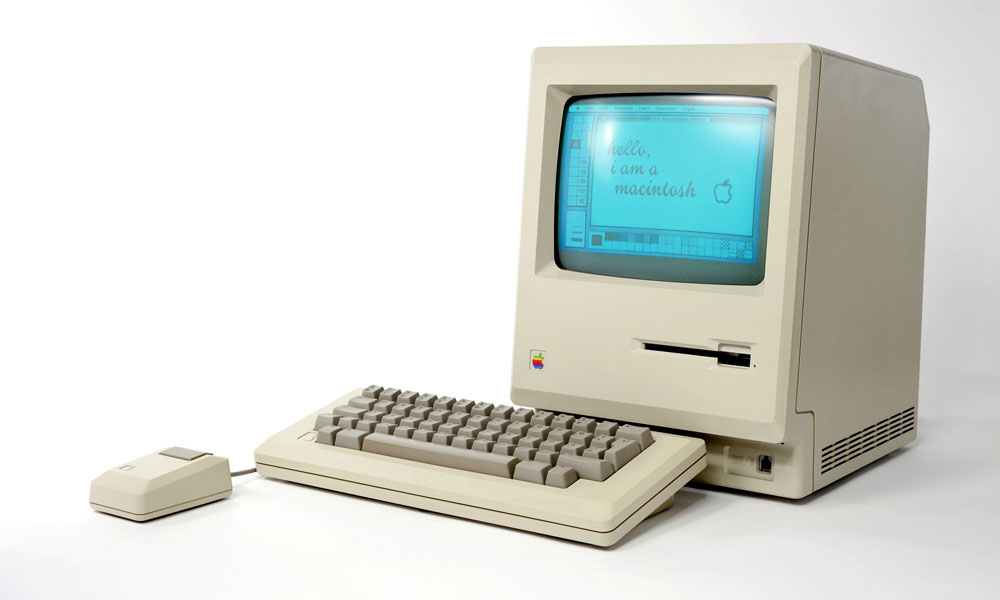

That ad, the Ridley Scott-directed “1984,” was an audacious play to convince the public that Apple’s newest computer, the Macintosh, was the future. When it aired during the Super Bowl 30 years ago this month, the Blade Runner director’s commercial brought a kind of dystopian, artistic mindset to an industry sector then known for fairly square advertising. (Don’t believe me? Here’s an IBM ad from the same era.) The Mac was meant to blow minds and change the world.

And it did. But not right away.

Mac Wasn’t Built in a Day

Something that gets lost in the vats of digital ink spilled about Apple over the years is that although the benefits of the Mac’s landmark graphical interface were certainly clear, it took a long time for those benefits to reach the general public.

Despite a pretty mind-blowing launch (cemented by the great Steve Jobs presentation, shown above), the device tried to compete directly with a well-entrenched competitor with decades of business mindshare, all while selling a completely new approach to the public. In the pre-internet world, this didn’t come easy. As noted in a retrospective piece on CNET, the company went to great lengths to sell people on the idea of using the devices—even at one point allowing potential consumers to bring the machines home for a 24-hour test drive.

(Oh, yeah: With no blogs to drive enthusiast interest, Apple also played a pivotal role in launching a magazine for the budding platform, the still-active Macworld. Sound like something your association has done?)

But a focus group showed that while users liked using the Mac far more than an IBM PC, ultimately business users picked Big Blue when asked which device they would most likely buy for a business department.

“Even though we had an incredibly innovative computer that appealed to the masses, IBM owned business,” Mike Murray, the head of the Macintosh marketing team at the time, said of the challenges posed by the competition.

And when it came down to it, the early PR wasn’t enough to gloss over the initial device’s weaknesses, which included a black-and-white screen and a microscopic amount of memory. The Mac, for decades, owned a few specific niches, notably education and graphic design. But when the graphical user interface (GUI) finally reached a mass audience in the business world, it was ultimately Microsoft that introduced it to a wide swath of the public—and even in that case, it wasn’t until Windows 3.0 that the product really started cooking with gas.

If you look back 30 years, you’ll see Apple’s biggest early Mac successes came from marketing narrowly—in industry sectors where early buy-in meant long-term influence.

So What Happened?

Every time I think about the Mac’s launch, I go back to the 2010 debut of the iPad—a device that also benefited from a huge PR push but that a lot of tech-minded folks didn’t find all that innovative at first. But here we are in 2014 and, with the Mac increasingly common in the office, the iPad still outsells it three to one.

Keeping in mind the differences between the market then and now (a blog-driven hype machine, for one thing; a market driven by consumers rather than businesses, for another), both devices represented a paradigm change, but only one drew immediate, lasting impact.

What gives? Well, part of it is that, for all the Mac’s innovations, it just didn’t have the ecosystem to make it a viable business offering. Apple was the first mover on the GUI—the Lisa, released a year earlier, got there before the Mac, but it was insanely expensive and not insanely great—but at the time Apple didn’t have the apps or the vendor lock-in that made it a smart move for a business to push an entire department to the Mac then and there.

The iPad had near-instant buy-in because there was already a mature development ecosystem and the devices offered backward compatibility with the iPhone. Mac OS, for all its innovation, was starting fresh. If you look at the trajectories of Apple’s category-launching platforms, the ones that started with no ecosystem—the iPhone and the iPod—took a little while to saturate the market. The iPod wasn’t really a hit until its third generation, for example.

And if you look back 30 years, you’ll see Apple’s biggest early Mac successes came from marketing narrowly—in industry sectors where early buy-in meant long-term influence. It focused its early efforts on universities, which led to entire generations of home users buying Macs because they got hooked at school. Apple allowed the Apple II to drive the profits while the Mac wrote the company’s next chapter. And, even during the platform’s weak periods, the company could always count on its inroads in the publishing and multimedia fields to keep it afloat. These moves gave the company a base to build upon.

Oh, sure, there were always naysayers, but the company kept at it, eventually riding the Mac to long-term success.

Tech Requires Buy-In

In recent months, I’ve developed a keen interest in content management systems from a hobbyist standpoint—closely following new platforms like Ghost and Harp to see what things are like on the other side of the coin. They’ve taken the lessons from all the bad that comes with CMSes and created fresh approaches that could provide a roadmap for the future of online content.

But I would never seriously suggest that associations switch their WordPress or Drupal-based website to either of these platforms at this juncture. Not because these new platforms aren’t potential game-changers, but because I know it’s asking a lot to persuade an organization to switch its web presence from something with broad support and years of history to something that’s untested and offers little in the way of a track record to work with.

Organizations have a lot of players. Leadership may be tentative. Changes require training, and the IT department needs a process to implement big things. And it’s understandable that the business world didn’t immediately jump just because Apple was holding the future in its hands. Apple had a couple of big misses before the Mac (ever hear about the Apple III?) and the Mac’s success wasn’t guaranteed. Apple had to earn that trust with the business world, and it took more than a few tries to pull it off.

Sometimes the best move is to wait, even if the future looks insanely great.

(iStock/Thinkstock)

Comments