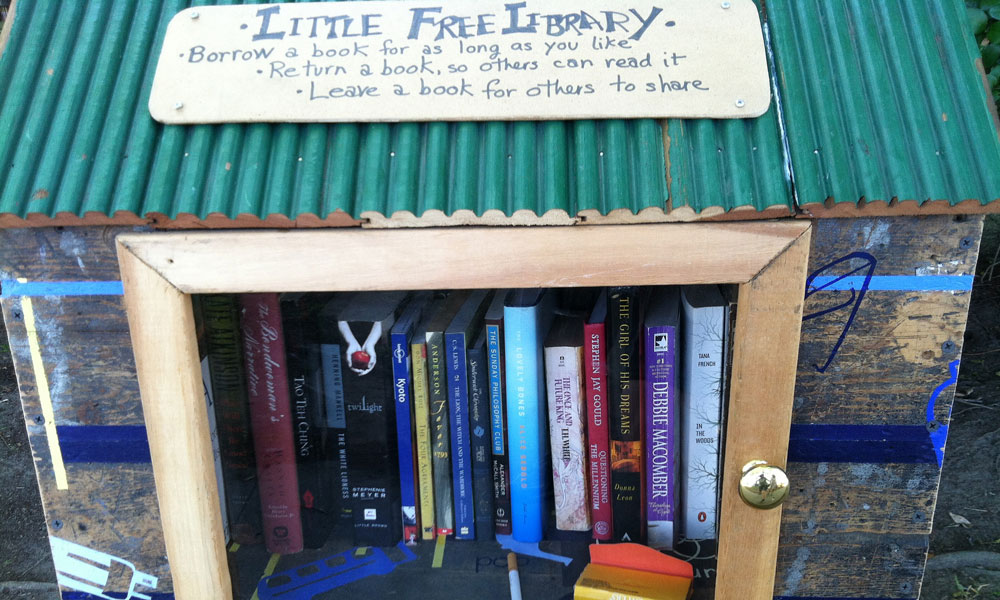

How the Little Free Library Became Hugely Influential

One guy's single spark of inspiration led to a global movement of book-sharing that has expanded far beyond its modest goals. Seven years after the first tiny schoolhouse went up on a post, Little Free Libraries are everywhere.

In an era where there’s always something new to read on a smartphone or laptop, the Little Free Library concept seems kind of antiquated.

But the movement—and the nonprofit that helped build it—has grown like a weed, and it has its roots in a very modern recession-era tale. In 2009, Wisconsinite Todd Bol lost his job and had a lot of time on his hands. He got the idea to build a tiny replica of a wooden schoolhouse, which he mounted in his front yard and filled with books, free for the taking.

People responded quickly to Bol’s idea.

“When I saw how people responded to the Little Free Library, my next question was: Would more people respond to it? Is this just a fluke of nature? Is it something in the air? Is it springtime?” Bol said of his early experiences, according to the Utne Reader. “As with most ideas, when you think you’ve got a decent one, what you have to say to yourself is, ‘How do I test this out?’”

Soon enough, Bol’s little idea was a major success, and, with the help of community sustainability expert Rick Brooks, he turned it into a nonprofit organization.

That decision launched a big movement. There are now 40,000 Little Free Libraries around the world, many in the United States, and some in places as far-flung as Armenia.

“Little Free Libraries have struck a chord internationally, because they celebrate reading, community, and creativity,” spokeswoman Margret Aldrich told The Post and Courier last month. “It’s truly become a global movement that welcomes everyone to be a part of it, whether you have a Little Free Library of your own or frequent one in your neighborhood.”

Dealing with red tape

But like every success story, this one comes with a few bumps in the road. In recent years, the movement has faced some regulatory challenges, most notably in 2014, when the city of Leawood, Kansas, forced 9-year-old Little Free Library owner Spencer Collins to take down his library, saying it violated a city ordinance prohibiting structures in front yards. The city council eventually relented in the face of negative media attention.

Collins isn’t the only one who has been challenged, but fortunately Little Free Libraries have some prominent voices among their defenders. Last year, popular Atlantic writer Conor Friedersdorf argued that “small-mindedness, inflexibility, and lack of common sense” has led local regulators to attempt to ban the structures.

For its part, Little Free Library responded to the Collins controversy by writing up a detailed blog post about zoning regulations and homeowners’ associations.

“We have found that City Council members, HOAs, and neighbors (even the grumpy ones) are all just people who can learn to love Little Libraries if you’re willing to work with them,” the nonprofit’s Megan Hanson wrote.

An Expanding Scale

Bol is still at the center of the movement as the executive director of the organization, which has helped to distribute more than 60 million books to readers around the world.

While the movement remains community-driven, the organization has a significant staff working on getting more tiny libraries into neighborhoods. Bol, who has done TED Talks about his little big idea, remains idealistic about its potential.

“We are a connector and a motivator of reading. We help spark a primal instinct in us, we have to be connected,” Bol told the Detroit Free Press in January. “It’s a better side of us. It’s a great side of ‘we’ … it’s bringing us back to our roots of who we are.”

(Michael R Perry/Flickr)

Comments